STACK service - Dask 101

This notebook introduces Dask's core APIs and demonstrates how to use them for scalable, parallel, and distributed data processing, culminating in deploying and interacting with a Dask cluster on the DestinE Data Lake STACK service.

Dask Core Library (APIs)¶

Dask provides several APIs, also called collections, to enable distributed+parallel execution on larger-than-memory datasets. We can think of Dask’s APIs at a high and a low level:

High-level collections: Dask provides high-level Array, Bag, and DataFrame collections that mimic NumPy, lists, and pandas but can operate in parallel on datasets that don’t fit into memory.

Low-level collections: Dask also provides low-level Tasks (Delayed and Futures) collections that give you finer control to build custom parallel and distributed computations.

In this tutorial we will focus on Dask Arrays and Tasks (Delayed and Futures). Please visit the Dask Examples and Dask Tutorial for additional information.

dask.array - parallelized numpy¶

Parallel, larger-than-memory, n-dimensional array using blocked algorithms.

Parallel: Uses all of the cores on your computer

Larger-than-memory: Lets you work on datasets that are larger than your available memory by breaking up your array into many small pieces, operating on those pieces in an order that minimizes the memory footprint of your computation, and effectively streaming data from disk.

Blocked Algorithms: Perform large computations by performing many smaller computations.

In other words, Dask Array implements a subset of the NumPy ndarray interface using blocked algorithms, cutting up the large array into many small arrays. This lets us compute on arrays larger than memory using all of our cores. We coordinate these blocked algorithms using Dask graphs.

In this notebook, we’ll build some understanding by implementing some blocked algorithms from scratch. We’ll then use Dask Array to analyze large datasets, in parallel, using a familiar NumPy-like API.

Related Documentation

Arrays - Example¶

A dask array looks and feels a lot like a numpy array. However, a dask array doesn’t directly hold any data. Instead, it symbolically represents the computations needed to generate the data. Nothing is actually computed until the actual numerical values are needed. This mode of operation is called “lazy”; it allows one to build up complex, large calculations symbolically before turning them over the scheduler for execution.

If we want to create a numpy array of all ones, we do it like this:

import numpy as np

shape = (1000, 4000)

ones_np = np.ones(shape)

ones_npThis array contains exactly 32 MB of data:

print('%.1f MB' % (ones_np.nbytes / 1e6))Now let’s create the same array using dask’s array interface.

import dask.array as da

ones = da.ones(shape)

onesThis works, but we didn’t tell Dask how to split up the array, so it is not optimized for distributed computation.

A crucial difference with Dask is that we must specify the chunks argument. “Chunks” describes how the array is split up over many sub-arrays.

There are several ways to specify chunks.

chunk_shape = (1000, 1000)

ones = da.ones(shape, chunks=chunk_shape)

onesNotice that we just see a symbolic representation of the array, including its shape, dtype, and chunksize. No data has been generated yet. When we call .compute() on a dask array, the computation is trigger and the dask array becomes a numpy array.

ones.compute()In order to understand what happened when we called .compute(), we can visualize the Dask graph, the symbolic operations, that make up the array.

ones.visualize(format='svg')The array has four chunks. To generate it, Dask calls np.ones four times and then concatenates this together into one array.

Rather than immediately loading a Dask array (which puts all the data into RAM), it is more common to reduce the data somehow. For example:

sum_of_ones = ones.sum()

sum_of_ones.visualize(format='svg')Here we see Dask’s strategy for finding the sum. This simple example illustrates the beauty of Dask: it automatically designs an algorithm appropriate for custom operations with big data.

If we make our operation more complex, the graph gets more complex.

fancy_calculation = (ones * ones[::-1, ::-1]).mean()

fancy_calculation.visualize(format='svg')dask.delayed - parallelize generic Python code¶

What if you don’t have an Dask array or Dask dataframe? Instead of having blocks where the function is applied to each block, you can decorate functions with @delayed and have the functions themselves be lazy. Rather than compute its result immediately, it records what needs to be computed as a task into a graph that we’ll run later on parallel hardware.

This is a simple way to use Dask to parallelize existing codebases or build complex systems.

Related Documentation

A typical workfow Read-Transform-Write workflow are most often implemented as outlined hereafter. In general, most workflows containing a for-loop can benefit from dask.delayed.

import dask

@dask.delayed

def process_file(filename):

data = read_a_file(filename)

data = do_a_transformation(data)

destination = f"results/{filename}"

write_out_data(data, destination)

return destination

results = []

for filename in filenames:

results.append(process_file(filename))

dask.compute(results)dask.delayed - Example¶

For demonstration purposes we will create simple functions to perform simple operations like add two numbers together, but they sleep for a random amount of time to simulate real work.

import time

def inc(x):

time.sleep(0.1)

return x + 1

def dec(x):

time.sleep(0.1)

return x - 1

def add(x, y):

time.sleep(0.2)

return x + yWe can run them like normal Python functions below

%%time

x = inc(1)

y = dec(2)

z = add(x, y)

zThese ran one after the other, in sequence. Note though that the first two lines inc(1) and dec(2) don’t depend on each other, we could have called them in parallel.

We can call dask.delayed on these funtions to make them lazy. Rather than compute their results immediately, they record what we want to compute as a task into a graph that we’ll run later on parallel hardware.

import dask

inc = dask.delayed(inc)

dec = dask.delayed(dec)

add = dask.delayed(add)Calling these lazy functions is now almost free. We’re just constructing a graph

%%time

x = inc(1)

y = dec(2)

z = add(x, y)

zVisualize computation

z.visualize(format='svg', rankdir='LR')Run in parallel. Call .compute() when you want your result as a normal Python object

%%time

z.compute()Parallelize Normal Python code

Now we use dask.delayed in a normal for-loop Python code as given in the example above. This generates graphs instead of doing computations directly, but still looks like the code we had before. Dask is a convenient way to add parallelism to existing workflows.

%%time

zs = []

for i in range(256):

x = inc(i)

y = dec(x)

z = add(x, y)

zs.append(z)

zs = dask.persist(*zs) # trigger computation in the backgroundDask Cluster (dask.distributed)¶

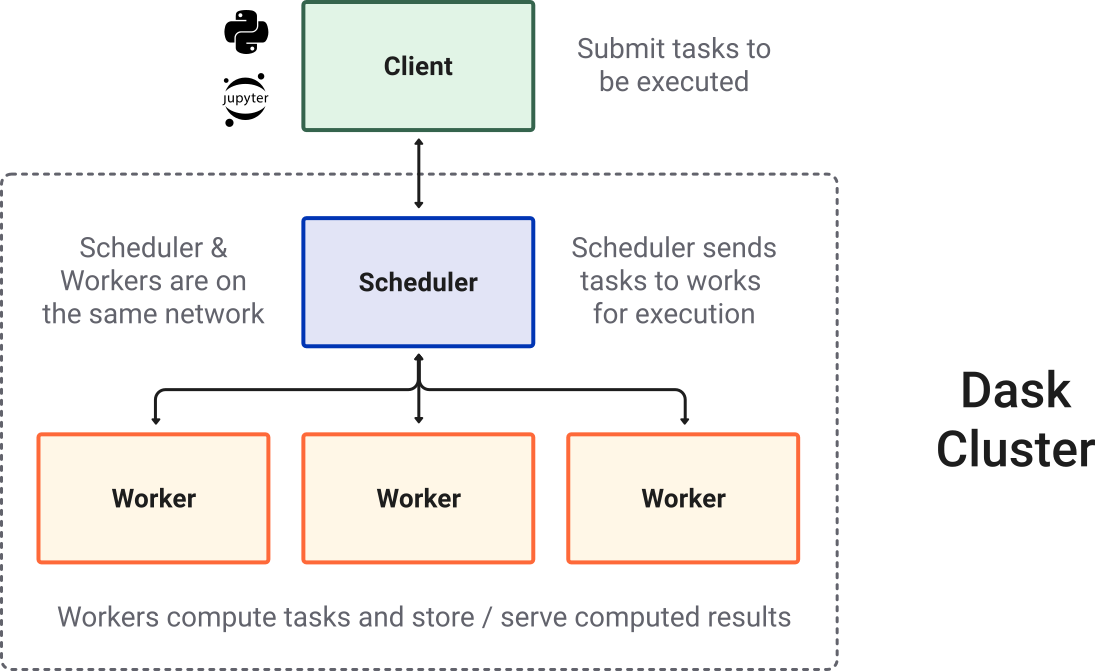

Dask has the ability to run work on multiple machines using the distributed scheduler. dask.distributed is a lightweight library for distributed computing in Python. It extends both the concurrent.futures and Dask APIs to run on various clusters technologies such as Kubernetes, Yarn, SLURM, PBS, etc. .

Most of the times when you are using Dask, you will be using a distributed scheduler, which exists in the context of a Dask cluster. When we talk about Dask Clusters we can think of those as depicted in the following:

Dask @ DEDL¶

DestinE Data Lake utilises a deployment of Dask Gateway on each location (bridge) in the data lake. Dask Gateway provides a secure, multi-tenant server for managing Dask clusters. It allows users to launch and use Dask clusters in a shared, centrally managed cluster environment, without requiring users to have direct access to the underlying cluster backend (e.g. Kubernetes, Hadoop/YARN, HPC Job queues, etc…).

Dask Gateway exposes a REST API to spawn clusters on demand. The overall architecture of Dask Gateway is depicted hereafter.

How to connect and spawn a cluster?¶

Central Site

proxy_address: tcp://dask.central.data.destination-earth.eu:80

LUMI Bridge

proxy_address: tcp://dask.lumi.data.destination-earth.eu:80

from dask_gateway.auth import GatewayAuth

from getpass import getpass

from destinelab import AuthHandler as DESP_AuthHandler

class DESPAuth(GatewayAuth):

def __init__(self, username: str):

self.auth_handler = DESP_AuthHandler(username, getpass("Please input your DESP password: "))

self.access_token = self.auth_handler.get_token()

def pre_request(self, _):

headers = {"Authorization": "Bearer " + self.access_token}

return headers, NoneOnly authenticated access is granted to the DEDL STACK service Dask, therefore a helper class to authenticate a user against the DESP identity management system is implemented. The users password is directly handed over to the request object and is not permanently stored.

In the following, please enter your DESP username and password. Again, the password will only be saved for the duration of this user session and will be remove as soon as the notebook/kernel is closed.

from rich.prompt import Prompt

myAuth = DESPAuth(username=Prompt.ask(prompt="Username"))from dask_gateway import Gateway

gateway = Gateway(address="http://dask.central.data.destination-earth.eu",

proxy_address="tcp://dask.central.data.destination-earth.eu:80",

auth=myAuth)Cluster creation and client instantiation to communicate with the new cluster

cluster = gateway.new_cluster()

client = cluster.get_client()

clusterUp to now the cluster will only consist of the distributed scheduler. If you want to spawn workers directly via Python adaptively, please use the following method call. With the following the cluster will be scaled to 2 workers initially. Depending on the load, Dask will add addtional workers, up to 5, if needed.

cluster.adapt(minimum=2, maximum=5)dask.futures - non-blocking distributed calculations¶

We will now make use of the remote Dask Cluster using the Dask low-level collection dask.futures.

Submit arbitrary functions for computation in a parallelized, eager, and non-blocking way.

The futures interface (derived from the built-in concurrent.futures) provide fine-grained real-time execution for custom situations. We can submit individual functions for evaluation with one set of inputs, or evaluated over a sequence of inputs with submit() and map(). The call returns immediately, giving one or more futures, whose status begins as “pending” and later becomes “finished”. There is no blocking of the local Python session.

Important

This is the important difference between futures and delayed. Both can be used to support arbitrary task scheduling, but delayed is lazy (it just constructs a graph) whereas futures are eager. With futures, as soon as the inputs are available and there is compute available, the computation starts.

Related Documentation

This is the same workflow that as given above in the dask.delayed section. It is a for-loop to iterate of certain files to perform a transformation and to write the result.

def process_file(filename):

data = read_a_file(filename)

data = do_a_transformation(data)

destination = f"results/{filename}"

write_out_data(data, destination)

return destination

futures = []

for filename in filenames:

future = client.submit(process_file, filename)

futures.append(future)

futuresfrom time import sleep

def inc(x):

sleep(1)

return x + 1We can run these function locally

inc(1)Or we can submit them to run remotely with Dask. This immediately returns a future that points to the ongoing computation, and eventually to the stored result.

future = client.submit(inc, 1) # returns immediately with pending future

futureIf you wait a second, and then check on the future again, you’ll see that it has finished.

futureYou can block on the computation and gather the result with the .result() method.

future.result()Other ways to wait for a future

from dask.distributed import wait, progress

progress(future)shows a progress bar in the notebook. This progress bar is also asynchronous, and doesn’t block the execution of other code in the meanwhile.

wait(future)blocks and forces the notebook to wait until the computation pointed to by future is done. However, note that if the result of inc() is sitting in the cluster, it would take no time to execute the computation now, because Dask notices that we are asking for the result of a computation it already knows about. More on this later.

Other ways to gather results

client.gather(futures)gathers results from more than one future.

from dask.distributed import wait, progress

def inc(x):

sleep(1)

return x + 1

future_x = client.submit(inc, 1)

future_y = client.submit(inc, 2)

future_z = client.submit(sum, [future_x, future_y])

progress(future_z)cluster.close(shutdown=True)